Words

No (1)

1992-1993

Whitney Murders

1978

Writing things down—in diaries, on the backs of drawings, and on countless sheets of paper—served the same function for Louise Bourgeois as making sculpture did; both were used to harness her unpredictable emotions and give them a form outside herself. Keenly sensitive to language and highly articulate, Bourgeois loved dictionaries, where she checked precise meanings and nuance. She interspersed English and French seamlessly in her writings, and also when she spoke.

While writing remained a daily activity for most of Bourgeois’s life, especially during long sleepless nights, the period of the 1950s into the 1960s is remarkable for the voluminous notes she made while undergoing psychoanalysis. While she was suffering from severe depression, her sculptural activity came to a halt but her writing flourished. Over a thousand loose sheets, filled with rhythmic lists of words, phrases, names, and brief texts, make an astounding literary compendium.

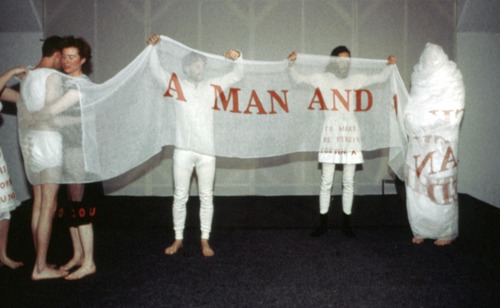

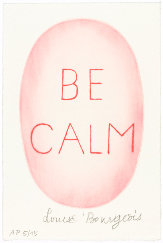

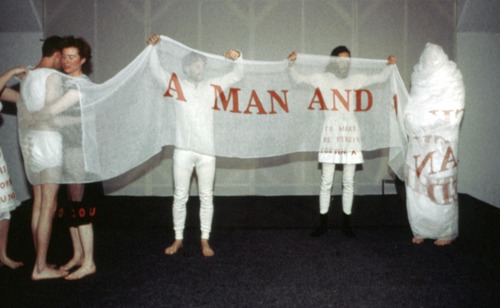

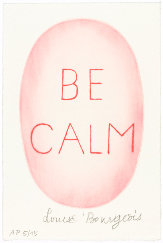

In 1992 one of Bourgeois’s parables, She Lost It, became the basis for a performance. She screenprinted the text onto a nearly 200-foot-long banner, in which she wrapped and unwrapped performers outfitted in costumes embroidered with her aphorisms. Her storytelling also appears in illustrated books, none more celebrated than He Disappeared into Complete Silence, of 1947. Many prints demonstrate how she made visual use of words, whether shouting “No” for a protest march, expressing anger at being rejected for an exhibition at the Whitney Museum, or fashioning a sign for what she found difficult to say aloud: “I love you,” “We love you,” “Je t’aime.”

No (1)

1992-1993

Whitney Murders

1978

“You can stand anything if you write it down.”