Although Louise Bourgeois’s work takes many forms, veering from the representational to the abstract, her motivation remained remarkably consistent over the course of her long life. For her, art served as a means, a tool, and finally, she said, “a guarantee of sanity.” Motifs emerged in the process of harnessing her strong emotions and ultimately became visual metaphors for particular concerns and struggles. These motifs are grouped under the thematic headings cited here.

“These works do not illustrate...they are an exorcism... That is what I am after...to dig and to reveal.”

Abstraction

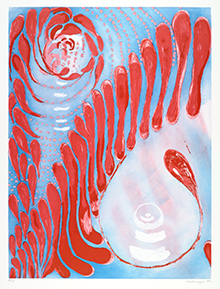

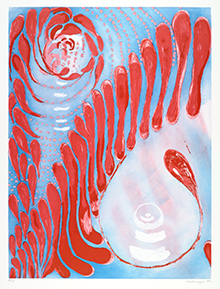

The art of Louise Bourgeois is most closely associated with provocative imagery, in the form of figures, body parts, spiders, and architectural structures. Yet abstraction plays a highly significant role overall. Printed grids, biomorphic ink drawings, and geometric wood totems are found in her early years, organically shaped marble and plaster sculptures come later, and an outpouring of abstract drawings and prints fills her last decade.

For Bourgeois, abstraction was yet another tool for understanding and coping with her feelings, which were always the driving forces of her art. She used terms like “calming,” “caressing,” or “stabbing” to describe strokes, and her drawn lines and evocative shapes reflect shifting moods and perceived vulnerabilities. Her methods harked back to the automatism of the Surrealists, in which compositions evolved intuitively with symbolic overtones. She often took advantage of repetition, drawing simple straight lines across sheets of notepads as she struggled with insomnia, thereby creating a diary of her fraught emotions.

Within the formats of printmaking—books, portfolios, and series—Bourgeois assembled abstract narratives, sometimes adding fragments of text. In fabric, her pages were fashioned from materials with stripes, plaids, or curvilinear patterns. The backdrop of music staves printed on paper provided another abstract foil for her rhythmic lines and shapes. In her last years, Bourgeois took up the technique of soft ground etching, which allowed her wavering touch to be sensitively captured. The result was a series of monumental abstract prints, often with hand-coloring, that are sometimes shown in room-scale installations.

Animals & Insects

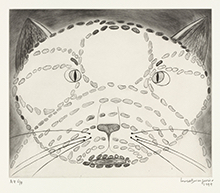

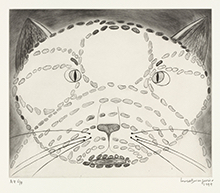

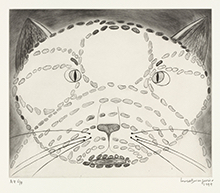

Creatures of the natural world were a source of fascination to Bourgeois from the time her father populated the family property with an assortment of hens, dogs, ducks, rabbits, pigs, and even a donkey, all meant to live in harmony. When she raised her own small boys, they spent time together observing nature at their weekend house in Easton, Connecticut, and also had family pets—cats named Tyger and Champfleurette, who appeared in Bourgeois’s dreams. Always attempting to decipher her own behavior and relationships, she looked to animals and insects for qualities they might share with humans.

Some of Bourgeois’s early paintings show plants and animals, and living things are also implied in the nests and lairs she shaped from plaster in the 1960s. Later works include fierce depictions of a flayed Rabbit in 1970, and a monstrous half-dog, half-mythic female titled She-Fox, in 1985. Such motifs appear only occasionally in her sculpture but take a distinctive place within her more intimate prints and drawings, where one finds a bestiary of cows, horses, pigs, cats, mosquitoes, and even an exotic llama. Spiders—actually classified as arachnids—form a separate category.

The artist anthropomorphizes this subject matter, particularly the wily cat. She invents a feline Self Portrait with five legs to help maintain stability. Champfleurette, the family pet, becomes a beguiling temptress who sports high-heels. Even Mosquito, the insect she dreaded as a summer pest, is seen with radiating locks, breasts, and a fetus.

Architecture

The architecture of New York City had an immediate impact on Louise Bourgeois when she arrived from France in 1938, newly married to American art historian Robert Goldwater. Her first print, a holiday greeting card for that year, shows fragments of both her new home and the Paris she left behind. New York’s skyscrapers also underlie the visual narratives that unfold in her celebrated illustrated book He Disappeared into Complete Silence, of 1947. She said, “My skyscrapers reflect a human condition,” and here they became personifications of loneliness, alienation, anger, and hostility. At that time, Bourgeois also created her Femme Maison, depicting a female body topped by a house. It became a feminist icon and was later issued as a print.

The architectural forms in Bourgeois’s early paintings and prints evolved into totem-like wood figures for her sculptural debut in the late 1940s. Dwellings of one form or another became ongoing motifs—from organically shaped plaster lairs in the 1960s to room-scale enclosures called Cells that dominated the later years. All these works are sites of personal dramas, where Bourgeois gave symbolic form to her vivid memories and powerful emotions. She even meticulously re-created particular buildings in marble—for example, her childhood home in Choisy-le-Roi, France, and New York’s Institute of Fine Arts, where her husband worked—placing them in assembled environments. For Bourgeois, who had initially trained in mathematics, architecture offered order, structure, and stability for tumultuous states of mind.

Body Parts

In the 1940s, Louise Bourgeois began an investigation of the partial female nude in a series of paintings, all titled Femme Maison (Woman House), in which houses substitute for heads. These images became feminist icons and subsequently turned up in her sculpture. Later, Bourgeois’s marble works of the 1960s and 1970s were filled with forms resembling breasts, penises, and undulating landscapes, all simultaneously. “Our own body could be considered from a topographical point of view,” she said, “a land with mounds and valleys, and caves and holes.” Latex proved a supple material in which to cast such shapes, culminating in the notorious Fillette (Little Girl), an unmistakable penis, nearly two feet high, hung by a hook from the ceiling.

In the 1970s, Bourgeois exhibited The Destruction of the Father, a claustrophobic, room-size lair crammed with bulbous, erotically charged latex protuberances and scattered animal limbs. She followed up with Confrontation, a stage-like setting accompanied by a performance titled A Banquet/A Fashion Show of Body Parts. She later shifted from merely suggesting body parts to creating more realistic depictions. Her sculptures, drawings, and prints of eyes, ears, hands, and lips all accentuate the functions of the senses, but in their disembodiment also conjure up the eerie Surrealist world of dreams and nightmares. In the 1990s, Bourgeois filled architectural Cells with assemblages of objects, among them marble sculptures of body fragments. Finally, late in life, she created larger-than-life-size stuffed fabric heads, which seem to grimace from the pains of old age.

Fabric Works

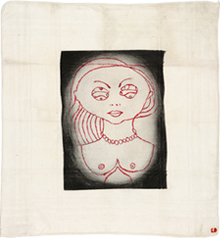

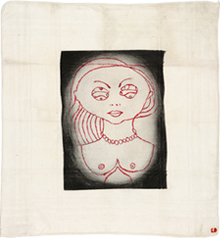

Louise Bourgeois’s connection to fabric goes back to her childhood years when she helped out in her family’s tapestry restoration workshop. As an adult, she long associated the act of sewing with repairing on a symbolic level, as she attempted to fix the damage she caused in personal relationships. She even held a special regard for spools of thread and needles as tools that served this purpose.

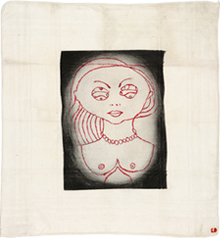

Fabric took center stage as a sculptural element in Bourgeois’s work in the 1990s, as she began to mine material from clothes accumulated over a lifetime. She hung old dresses, slips, and nightwear in installations, and then manipulated timeworn terry cloth into nearly life-size figures or eerie portrait-like heads. In 1999, she hired a seamstress, Mercedes Katz, to help with this work and set her up in a workshop-like area on the lower level of her house, where she also installed two small printing presses. By 2000, Bourgeois had turned to printing on old handkerchiefs, and then other fabrics. She also constructed books of fabric collages.

Printing on fabric was a major preoccupation of Bourgeois’s later years and she highly valued her collaboration with Katz and the various printers with whom she worked. The old fabrics she selected resonated with memories yet, on occasion, she ran out of material when making an edition and had to seek out matching fabrics. To this same end, she sometimes took advantage of digital possibilities for duplicating aging or fading effects. In contrast to her prints and books on paper, Bourgeois’s fabric works have a tactile presence that gives them a decidedly sculptural dimension.

Faces & Portaits

A “drama of the self” is how Louise Bourgeois once described a work, perceiving her art overall as a form of self-portraiture. The characters in this drama occasionally included family members, most memorably her mother who appears as a spider. But, most often, it was her own emotions that Bourgeois transformed into “portraits.” She became the threatening Femme Couteau (Knife Woman), the stifled Femme Maison (Woman House), or the flirtatious Femme Volage (Fickle Woman). Bourgeois also showed herself in various configurations as The Bad Mother. In Bosom Lady, of 1948, she observed that three eggs in a bowl near a bird-woman are her “jewels”—her three children. But she also pointed out that this figure could easily “escape by flight.”

Bourgeois revealed her fears, anger, and despair most vividly in depictions of the human face. She called these “portraits of a mood,” and painful emotions are often communicated through contorted expressions or dizzying eyes. Very long hair—a pride of Bourgeois’s for most of her life—became a symbol of sexuality that could represent seduction, entanglement, or vulnerability. In the early 2000s, in a powerful expression of old age, Bourgeois created a series of fabric sculptures of heads that seem to cry out or grimace in pain. Then, in her last year, she issued Self Portrait, a series of 24 drypoints on fabric portraying various interpretations of her life from birth to adulthood. She also sewed these prints in a clock shape on a single piece of fabric, clearly evoking the passage of time.

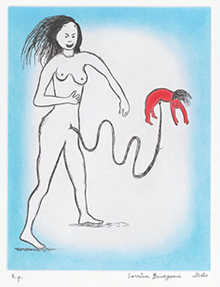

Figures

The motif of the human figure served as an embodiment of changing moods and desires for Louise Bourgeois throughout her career. Early on, she painted, drew, and printed intimate scenes of family life—her husband reading, her children in the tub, herself setting the table. Her first sculptures, in the late 1940s, were abstracted wood totems that represented people she left behind in France. She called them “personages,” and similar figures appear in her prints of that time.

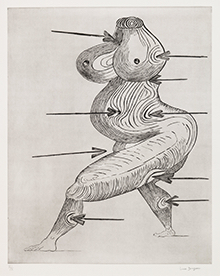

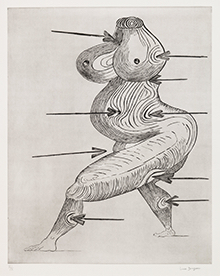

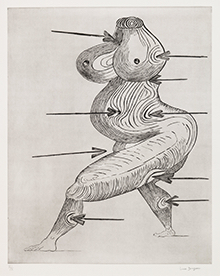

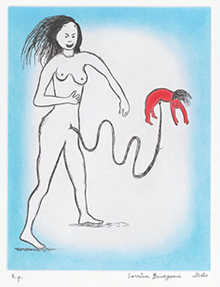

Later, Bourgeois turned to sculptures of organically shaped body parts that morphed between genders, and from human to landscape forms. She released her aggression in a series of female figures fashioned as weapons, titled Femme Couteau (Knife Woman). By the 1990s, her previously abstracted figural shapes took on a heightened realism. The monumental drypoint Sainte Sébastienne is an explicit representation of the pain she perceived from personal attacks. She said of her artistic strategy, “If I want to express something of immediate, all-consuming importance…I will make a piece that is inspired by a very strong desire to stand in,” for it.

Bourgeois’s repertoire of figures expanded up until her last years, and included recurring images of couples, in all mediums, that reflect a provocative sexuality for which she was well-known. She focused, as well, on the act of giving birth. In prints and drawings, her female figures often display flowing locks that denote both attraction and entrapment and serve as a sign of self-portraiture, since Bourgeois kept her hair very long for most of her life.

Motherhood & Family

Among Louise Bourgeois’s most symbolic titles is One and Others, referring to a preoccupation with personal relationships that motivated much of her art. She constantly struggled with a need for attachments, yet she experienced difficulty and ambivalence when dealing with those around her, most significantly her parents, siblings, husband, and children. Her memories of her mother and father never dimmed and found expression in countless works, as significant as the spiders that represented her meticulous mother, or the room-size tableau, The Destruction of the Father, that evokes violence and anger.

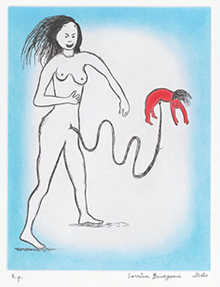

Upon the births of her own children, Bourgeois felt a profound sense of gratitude but was overwhelmed by feelings of inadequacy. “There I was,” she said, “a wife and mother, and I was afraid of my family…afraid not to measure up.” She relived the birth experience in her art time and again—her own birth and that of her children—never more so than in the last decade of her life. Among her representations is a mother with an umbilical cord that remains attached to a baby.

Bourgeois also recalled simple family life of the 1940s, when her children were young, reinterpreting drawings of that period in new printed images. For her, it was as if no time had passed when she created an aquatint and drypoint in the 1990s depicting two of her small boys in the tub. Similarly, she assembled the illustrated book Album in 1994, gathering together nearly 70 snapshots from her long-ago childhood that encapsulated that earlier time.

Music

Children’s songs, piano lessons, and records were intimate memories of growing up for Louise Bourgeois. In a diary entry from 1950 she listed old family recordings she came across in the attic—mostly operas, but also popular French songs of the day. Later, in old age, music was a comfort. Listening to it at night calmed her during bouts of insomnia, and she found humming or singing songs from the past to be soothing.

For Bourgeois, musical rhythms provided reliability, something she deeply appreciated but found elusive in herself. She relished her metronome and kept it close by on her work desk, among her pens, pencils, brushes, and paper. The voluminous notes she wrote in diaries and on the backs of drawings often contain words that read like free-associative lyrics: “…rain, water can, water tap, kettle, moss, splash, waddle, puddle, mud pies, muddle, drip, leak, pump, dry well….” Other handwritten lists hint at her musical tastes: “Mozart, La Flute enchantée, Buddy Holly, Houston Texas yodels, Rolling Stones, Chuck Berry, Hardbreak Hotel, I Get So Lonely I Could Die.”

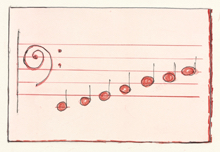

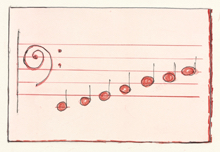

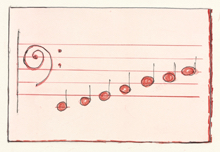

Printed music paper became a major element in Bourgeois’s work in the mid-1990s, with a series called The Insomnia Drawings. The horizontal staves provided a visual rhythm and also a foil against which to react. They form the backdrop for her Fugue portfolio of 2002–05, where squares, circles, lines, and spirals suggest reverberating sounds. Also during these late years, Bourgeois issued two CDs capturing her own brand of singing and inventive lyrics.

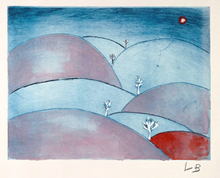

Nature

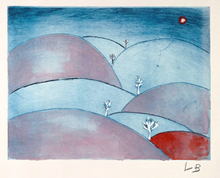

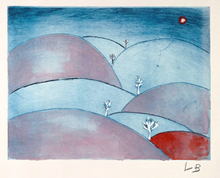

Trees, flowers, nests, mountains, rivers, and clouds are among the elements of nature to which Louise Bourgeois looked for expressions of procreation, growth, and refuge, as well as unsettling states of mind. The natural terrain also became a metaphor for the human body. “It seems rather evident to me,” she said, “that our own body is a figuration that appears in Mother Earth.”

While growing up, Bourgeois and her siblings each had a garden plot where they planted roses and geraniums and tended to apple and pear trees. Later she explored the workings of nature with her own children at their country house in Easton, Connecticut. This preoccupation with the natural world shows itself in her work at various intervals, particularly in the 1960s, when she fashioned cocoons and lairs of plaster, and bulbous landscapes of marble, latex, and hardened plastics. This turn to mutable, biomorphic forms was in stark contrast to the rigid wood figures she created in the 1940s and 1950s, or the architectural structures that became her Cells series in later years.

Bourgeois’s prints, drawings, and illustrated books of the 1990s and 2000s are filled with references to nature. The Bièvre River in France is the subject of a book of abstract fabric collages, and Les Arbres, a series of six portfolios, mines the symbolic potential of mountains, trees, branches, and leaves in drypoint and watercolor. In 2008, an exhibition of Bourgeois’s work, titled Nature Study, took place in the Royal Botanic Gardens of Scotland, where it was coupled with 19th-century botanical drawings from the Gardens' archive.

Objects

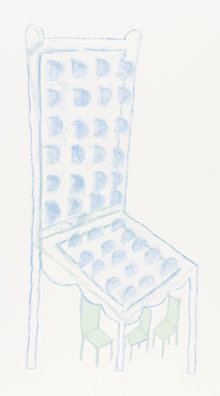

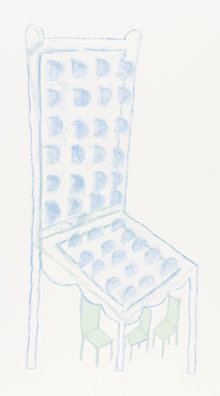

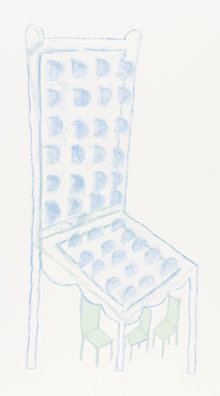

Transformation is at the core of Bourgeois’s treatment of objects as artistic motifs. In her very early prints, chairs, tables, clocks, bathtubs, and storage cabinets take on amplified meanings as they loom large in her depicted world and share space with family members. In the later 1940s and 1950s, she shifted to figural presences, which would dominate her sculpture.

Her practice of imbuing common objects with symbolic functions becomes palpable in sculptures of the late 1960s, like the fierce marble Femme Couteau, in which a woman turns herself into a knife, or the equally threatening bronze object Molotov Cocktail, a vivid reference to the rioters of the era. For Bourgeois, “Symbols are indispensable...these things are very, very clear, very simple—and absolutely devastating.”

Bourgeois filled her Cells of the 1990s and 2000s with a variety of everyday objects gathered from her house or studio, most saved for many years. She carefully placed perfume bottles, spools of thread, mirrors, lanterns, and old furnishings like tables, chairs, stools, and beds in close proximity to her sculptural works, giving all these objects added resonance. They are further transformed by the contexts of these strange room-like structures. In later prints and drawings, Bourgeois gave objects anthropomorphic qualities. Scissors are seen giving birth to baby scissors in one drypoint and aquatint, and an eroticized bed is the primary subject of a large group of printed compositions. Bourgeois described beds as “erotic objects…where you lie with your husband, where your children were born and you will die.”

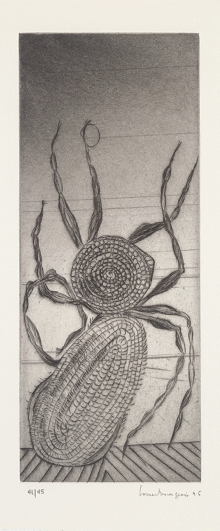

Spiders

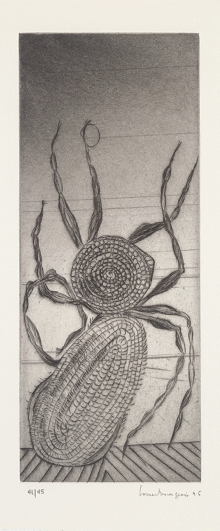

Although recognized for exploring a broad array of materials and motifs, Louise Bourgeois is perhaps best known for sculptures of spiders, ranging in size from a brooch of four inches to monumental outdoor pieces that rise to 30 feet. Long a motif in Symbolist art, the spider encompassed several meanings for Bourgeois, who cited it most frequently as a stand-in for her mother, a tapestry restorer by trade who impressed Bourgeois with her steadfast reliability and clever inventiveness. Yet Bourgeois also appreciated the spider in more general terms, as a protector against evil, pointing out that this crafty arachnid is known for devouring mosquitoes and thereby preventing disease.

Bourgeois’s preoccupation with the spider spans her career, with examples appearing in her drawing and printmaking as early as the late 1940s, but the subject began to have a particular immediacy for her in the mid-1990s. Among the defining projects of that time is Ode à Ma Mère, a 1995 illustrated book comprised of drypoint spiders, along with a text evoking the complicated interpretations Bourgeois framed for them. Bourgeois continued to explore this theme in sculpture, drawing, and printmaking until late in her life. In 2007, she crafted a woven fabric example and also issued a series of digital prints incorporating spiders. That late series, entitled The Fragile, presents her subject in a variety of guises, often merging with a female figure and evoking the aging artist herself.

Spirals

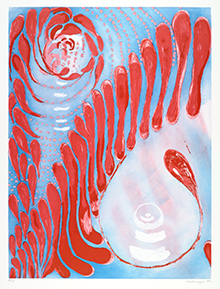

Within Louise Bourgeois’s overall investigation of abstract motifs, the spiral holds a distinct place, recurring across her oeuvre. It is found in segmented wood sculptures of the early 1950s that twist and turn, in a plaster mound from the 1960s that suggests a tomb monument, and in a bronze figure of the 1980s that struggles inside a cocoon and hangs precariously from the ceiling by a string. Numerous drawings and prints add to this evocative repertoire. In the 1990s, Bourgeois even created a performance piece, She Lost It, in which she wrapped and unwrapped her performers in a spiraling gauze banner, nearly 200 feet long, printed with one of her parables.

To describe the symbolic resonance spirals held for her, Bourgeois harked back to her childhood, when she watched the workers in her family’s tapestry restoration business wash tapestries in the river and then fiercely wring them out. She segued easily from this recollection to the fantasy of wringing the neck of someone she despised. But in fact, the spiral functioned as a visual metaphor for a range of her emotions, not just anger.

Bourgeois stressed the spiral’s two opposing directions: inward and outward. The outward movement represented “giving, and giving up control, trust and positive energy….” While the winding in of the spiral embodied “a tightening, a retreating, a compacting to the point of disappearance.” She said, “You can get twisted and strangled by your emotions.” Always reflecting her volatile temperament, Bourgeois’s spirals are endlessly variable—as coils of tension, protective cocoons, and even entrapping spider webs.

Words

Writing things down—in diaries, on the backs of drawings, and on countless sheets of paper—served the same function for Louise Bourgeois as making sculpture did; both were used to harness her unpredictable emotions and give them a form outside herself. Keenly sensitive to language and highly articulate, Bourgeois loved dictionaries, where she checked precise meanings and nuance. She interspersed English and French seamlessly in her writings, and also when she spoke.

While writing remained a daily activity for most of Bourgeois’s life, especially during long sleepless nights, the period of the 1950s into the 1960s is remarkable for the voluminous notes she made while undergoing psychoanalysis. While she was suffering from severe depression, her sculptural activity came to a halt but her writing flourished. Over a thousand loose sheets, filled with rhythmic lists of words, phrases, names, and brief texts, make an astounding literary compendium.

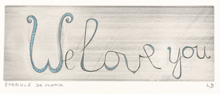

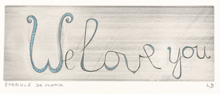

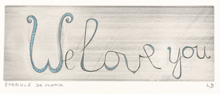

In 1992 one of Bourgeois’s parables, She Lost It, became the basis for a performance. She screenprinted the text onto a nearly 200-foot-long banner, in which she wrapped and unwrapped performers outfitted in costumes embroidered with her aphorisms. Her storytelling also appears in illustrated books, none more celebrated than He Disappeared into Complete Silence, of 1947. Many prints demonstrate how she made visual use of words, whether shouting “No” for a protest march, expressing anger at being rejected for an exhibition at the Whitney Museum, or fashioning a sign for what she found difficult to say aloud: “I love you,” “We love you,” “Je t’aime.”

Abstraction

The art of Louise Bourgeois is most closely associated with provocative imagery, in the form of figures, body parts, spiders, and architectural structures. Yet abstraction plays a highly significant role overall. Printed grids, biomorphic ink drawings, and geometric wood totems are found in her early years, organically shaped marble and plaster sculptures come later, and an outpouring of abstract drawings and prints fills her last decade.

For Bourgeois, abstraction was yet another tool for understanding and coping with her feelings, which were always the driving forces of her art. She used terms like “calming,” “caressing,” or “stabbing” to describe strokes, and her drawn lines and evocative shapes reflect shifting moods and perceived vulnerabilities. Her methods harked back to the automatism of the Surrealists, in which compositions evolved intuitively with symbolic overtones. She often took advantage of repetition, drawing simple straight lines across sheets of notepads as she struggled with insomnia, thereby creating a diary of her fraught emotions.

Within the formats of printmaking—books, portfolios, and series—Bourgeois assembled abstract narratives, sometimes adding fragments of text. In fabric, her pages were fashioned from materials with stripes, plaids, or curvilinear patterns. The backdrop of music staves printed on paper provided another abstract foil for her rhythmic lines and shapes. In her last years, Bourgeois took up the technique of soft ground etching, which allowed her wavering touch to be sensitively captured. The result was a series of monumental abstract prints, often with hand-coloring, that are sometimes shown in room-scale installations.

Architecture

The architecture of New York City had an immediate impact on Louise Bourgeois when she arrived from France in 1938, newly married to American art historian Robert Goldwater. Her first print, a holiday greeting card for that year, shows fragments of both her new home and the Paris she left behind. New York’s skyscrapers also underlie the visual narratives that unfold in her celebrated illustrated book He Disappeared into Complete Silence, of 1947. She said, “My skyscrapers reflect a human condition,” and here they became personifications of loneliness, alienation, anger, and hostility. At that time, Bourgeois also created her Femme Maison, depicting a female body topped by a house. It became a feminist icon and was later issued as a print.

The architectural forms in Bourgeois’s early paintings and prints evolved into totem-like wood figures for her sculptural debut in the late 1940s. Dwellings of one form or another became ongoing motifs—from organically shaped plaster lairs in the 1960s to room-scale enclosures called Cells that dominated the later years. All these works are sites of personal dramas, where Bourgeois gave symbolic form to her vivid memories and powerful emotions. She even meticulously re-created particular buildings in marble—for example, her childhood home in Choisy-le-Roi, France, and New York’s Institute of Fine Arts, where her husband worked—placing them in assembled environments. For Bourgeois, who had initially trained in mathematics, architecture offered order, structure, and stability for tumultuous states of mind.

Fabric Works

Louise Bourgeois’s connection to fabric goes back to her childhood years when she helped out in her family’s tapestry restoration workshop. As an adult, she long associated the act of sewing with repairing on a symbolic level, as she attempted to fix the damage she caused in personal relationships. She even held a special regard for spools of thread and needles as tools that served this purpose.

Fabric took center stage as a sculptural element in Bourgeois’s work in the 1990s, as she began to mine material from clothes accumulated over a lifetime. She hung old dresses, slips, and nightwear in installations, and then manipulated timeworn terry cloth into nearly life-size figures or eerie portrait-like heads. In 1999, she hired a seamstress, Mercedes Katz, to help with this work and set her up in a workshop-like area on the lower level of her house, where she also installed two small printing presses. By 2000, Bourgeois had turned to printing on old handkerchiefs, and then other fabrics. She also constructed books of fabric collages.

Printing on fabric was a major preoccupation of Bourgeois’s later years and she highly valued her collaboration with Katz and the various printers with whom she worked. The old fabrics she selected resonated with memories yet, on occasion, she ran out of material when making an edition and had to seek out matching fabrics. To this same end, she sometimes took advantage of digital possibilities for duplicating aging or fading effects. In contrast to her prints and books on paper, Bourgeois’s fabric works have a tactile presence that gives them a decidedly sculptural dimension.

Figures

The motif of the human figure served as an embodiment of changing moods and desires for Louise Bourgeois throughout her career. Early on, she painted, drew, and printed intimate scenes of family life—her husband reading, her children in the tub, herself setting the table. Her first sculptures, in the late 1940s, were abstracted wood totems that represented people she left behind in France. She called them “personages,” and similar figures appear in her prints of that time.

Later, Bourgeois turned to sculptures of organically shaped body parts that morphed between genders, and from human to landscape forms. She released her aggression in a series of female figures fashioned as weapons, titled Femme Couteau (Knife Woman). By the 1990s, her previously abstracted figural shapes took on a heightened realism. The monumental drypoint Sainte Sébastienne is an explicit representation of the pain she perceived from personal attacks. She said of her artistic strategy, “If I want to express something of immediate, all-consuming importance…I will make a piece that is inspired by a very strong desire to stand in,” for it.

Bourgeois’s repertoire of figures expanded up until her last years, and included recurring images of couples, in all mediums, that reflect a provocative sexuality for which she was well-known. She focused, as well, on the act of giving birth. In prints and drawings, her female figures often display flowing locks that denote both attraction and entrapment and serve as a sign of self-portraiture, since Bourgeois kept her hair very long for most of her life.

Music

Children’s songs, piano lessons, and records were intimate memories of growing up for Louise Bourgeois. In a diary entry from 1950 she listed old family recordings she came across in the attic—mostly operas, but also popular French songs of the day. Later, in old age, music was a comfort. Listening to it at night calmed her during bouts of insomnia, and she found humming or singing songs from the past to be soothing.

For Bourgeois, musical rhythms provided reliability, something she deeply appreciated but found elusive in herself. She relished her metronome and kept it close by on her work desk, among her pens, pencils, brushes, and paper. The voluminous notes she wrote in diaries and on the backs of drawings often contain words that read like free-associative lyrics: “…rain, water can, water tap, kettle, moss, splash, waddle, puddle, mud pies, muddle, drip, leak, pump, dry well….” Other handwritten lists hint at her musical tastes: “Mozart, La Flute enchantée, Buddy Holly, Houston Texas yodels, Rolling Stones, Chuck Berry, Hardbreak Hotel, I Get So Lonely I Could Die.”

Printed music paper became a major element in Bourgeois’s work in the mid-1990s, with a series called The Insomnia Drawings. The horizontal staves provided a visual rhythm and also a foil against which to react. They form the backdrop for her Fugue portfolio of 2002–05, where squares, circles, lines, and spirals suggest reverberating sounds. Also during these late years, Bourgeois issued two CDs capturing her own brand of singing and inventive lyrics.

Objects

Transformation is at the core of Bourgeois’s treatment of objects as artistic motifs. In her very early prints, chairs, tables, clocks, bathtubs, and storage cabinets take on amplified meanings as they loom large in her depicted world and share space with family members. In the later 1940s and 1950s, she shifted to figural presences, which would dominate her sculpture.

Her practice of imbuing common objects with symbolic functions becomes palpable in sculptures of the late 1960s, like the fierce marble Femme Couteau, in which a woman turns herself into a knife, or the equally threatening bronze object Molotov Cocktail, a vivid reference to the rioters of the era. For Bourgeois, “Symbols are indispensable...these things are very, very clear, very simple—and absolutely devastating.”

Bourgeois filled her Cells of the 1990s and 2000s with a variety of everyday objects gathered from her house or studio, most saved for many years. She carefully placed perfume bottles, spools of thread, mirrors, lanterns, and old furnishings like tables, chairs, stools, and beds in close proximity to her sculptural works, giving all these objects added resonance. They are further transformed by the contexts of these strange room-like structures. In later prints and drawings, Bourgeois gave objects anthropomorphic qualities. Scissors are seen giving birth to baby scissors in one drypoint and aquatint, and an eroticized bed is the primary subject of a large group of printed compositions. Bourgeois described beds as “erotic objects…where you lie with your husband, where your children were born and you will die.”

Spirals

Within Louise Bourgeois’s overall investigation of abstract motifs, the spiral holds a distinct place, recurring across her oeuvre. It is found in segmented wood sculptures of the early 1950s that twist and turn, in a plaster mound from the 1960s that suggests a tomb monument, and in a bronze figure of the 1980s that struggles inside a cocoon and hangs precariously from the ceiling by a string. Numerous drawings and prints add to this evocative repertoire. In the 1990s, Bourgeois even created a performance piece, She Lost It, in which she wrapped and unwrapped her performers in a spiraling gauze banner, nearly 200 feet long, printed with one of her parables.

To describe the symbolic resonance spirals held for her, Bourgeois harked back to her childhood, when she watched the workers in her family’s tapestry restoration business wash tapestries in the river and then fiercely wring them out. She segued easily from this recollection to the fantasy of wringing the neck of someone she despised. But in fact, the spiral functioned as a visual metaphor for a range of her emotions, not just anger.

Bourgeois stressed the spiral’s two opposing directions: inward and outward. The outward movement represented “giving, and giving up control, trust and positive energy….” While the winding in of the spiral embodied “a tightening, a retreating, a compacting to the point of disappearance.” She said, “You can get twisted and strangled by your emotions.” Always reflecting her volatile temperament, Bourgeois’s spirals are endlessly variable—as coils of tension, protective cocoons, and even entrapping spider webs.

Animals & Insects

Creatures of the natural world were a source of fascination to Bourgeois from the time her father populated the family property with an assortment of hens, dogs, ducks, rabbits, pigs, and even a donkey, all meant to live in harmony. When she raised her own small boys, they spent time together observing nature at their weekend house in Easton, Connecticut, and also had family pets—cats named Tyger and Champfleurette, who appeared in Bourgeois’s dreams. Always attempting to decipher her own behavior and relationships, she looked to animals and insects for qualities they might share with humans.

Some of Bourgeois’s early paintings show plants and animals, and living things are also implied in the nests and lairs she shaped from plaster in the 1960s. Later works include fierce depictions of a flayed Rabbit in 1970, and a monstrous half-dog, half-mythic female titled She-Fox, in 1985. Such motifs appear only occasionally in her sculpture but take a distinctive place within her more intimate prints and drawings, where one finds a bestiary of cows, horses, pigs, cats, mosquitoes, and even an exotic llama. Spiders—actually classified as arachnids—form a separate category.

The artist anthropomorphizes this subject matter, particularly the wily cat. She invents a feline Self Portrait with five legs to help maintain stability. Champfleurette, the family pet, becomes a beguiling temptress who sports high-heels. Even Mosquito, the insect she dreaded as a summer pest, is seen with radiating locks, breasts, and a fetus.

Body Parts

In the 1940s, Louise Bourgeois began an investigation of the partial female nude in a series of paintings, all titled Femme Maison (Woman House), in which houses substitute for heads. These images became feminist icons and subsequently turned up in her sculpture. Later, Bourgeois’s marble works of the 1960s and 1970s were filled with forms resembling breasts, penises, and undulating landscapes, all simultaneously. “Our own body could be considered from a topographical point of view,” she said, “a land with mounds and valleys, and caves and holes.” Latex proved a supple material in which to cast such shapes, culminating in the notorious Fillette (Little Girl), an unmistakable penis, nearly two feet high, hung by a hook from the ceiling.

In the 1970s, Bourgeois exhibited The Destruction of the Father, a claustrophobic, room-size lair crammed with bulbous, erotically charged latex protuberances and scattered animal limbs. She followed up with Confrontation, a stage-like setting accompanied by a performance titled A Banquet/A Fashion Show of Body Parts. She later shifted from merely suggesting body parts to creating more realistic depictions. Her sculptures, drawings, and prints of eyes, ears, hands, and lips all accentuate the functions of the senses, but in their disembodiment also conjure up the eerie Surrealist world of dreams and nightmares. In the 1990s, Bourgeois filled architectural Cells with assemblages of objects, among them marble sculptures of body fragments. Finally, late in life, she created larger-than-life-size stuffed fabric heads, which seem to grimace from the pains of old age.

Faces & Portaits

A “drama of the self” is how Louise Bourgeois once described a work, perceiving her art overall as a form of self-portraiture. The characters in this drama occasionally included family members, most memorably her mother who appears as a spider. But, most often, it was her own emotions that Bourgeois transformed into “portraits.” She became the threatening Femme Couteau (Knife Woman), the stifled Femme Maison (Woman House), or the flirtatious Femme Volage (Fickle Woman). Bourgeois also showed herself in various configurations as The Bad Mother. In Bosom Lady, of 1948, she observed that three eggs in a bowl near a bird-woman are her “jewels”—her three children. But she also pointed out that this figure could easily “escape by flight.”

Bourgeois revealed her fears, anger, and despair most vividly in depictions of the human face. She called these “portraits of a mood,” and painful emotions are often communicated through contorted expressions or dizzying eyes. Very long hair—a pride of Bourgeois’s for most of her life—became a symbol of sexuality that could represent seduction, entanglement, or vulnerability. In the early 2000s, in a powerful expression of old age, Bourgeois created a series of fabric sculptures of heads that seem to cry out or grimace in pain. Then, in her last year, she issued Self Portrait, a series of 24 drypoints on fabric portraying various interpretations of her life from birth to adulthood. She also sewed these prints in a clock shape on a single piece of fabric, clearly evoking the passage of time.

Motherhood & Family

Among Louise Bourgeois’s most symbolic titles is One and Others, referring to a preoccupation with personal relationships that motivated much of her art. She constantly struggled with a need for attachments, yet she experienced difficulty and ambivalence when dealing with those around her, most significantly her parents, siblings, husband, and children. Her memories of her mother and father never dimmed and found expression in countless works, as significant as the spiders that represented her meticulous mother, or the room-size tableau, The Destruction of the Father, that evokes violence and anger.

Upon the births of her own children, Bourgeois felt a profound sense of gratitude but was overwhelmed by feelings of inadequacy. “There I was,” she said, “a wife and mother, and I was afraid of my family…afraid not to measure up.” She relived the birth experience in her art time and again—her own birth and that of her children—never more so than in the last decade of her life. Among her representations is a mother with an umbilical cord that remains attached to a baby.

Bourgeois also recalled simple family life of the 1940s, when her children were young, reinterpreting drawings of that period in new printed images. For her, it was as if no time had passed when she created an aquatint and drypoint in the 1990s depicting two of her small boys in the tub. Similarly, she assembled the illustrated book Album in 1994, gathering together nearly 70 snapshots from her long-ago childhood that encapsulated that earlier time.

Nature

Trees, flowers, nests, mountains, rivers, and clouds are among the elements of nature to which Louise Bourgeois looked for expressions of procreation, growth, and refuge, as well as unsettling states of mind. The natural terrain also became a metaphor for the human body. “It seems rather evident to me,” she said, “that our own body is a figuration that appears in Mother Earth.”

While growing up, Bourgeois and her siblings each had a garden plot where they planted roses and geraniums and tended to apple and pear trees. Later she explored the workings of nature with her own children at their country house in Easton, Connecticut. This preoccupation with the natural world shows itself in her work at various intervals, particularly in the 1960s, when she fashioned cocoons and lairs of plaster, and bulbous landscapes of marble, latex, and hardened plastics. This turn to mutable, biomorphic forms was in stark contrast to the rigid wood figures she created in the 1940s and 1950s, or the architectural structures that became her Cells series in later years.

Bourgeois’s prints, drawings, and illustrated books of the 1990s and 2000s are filled with references to nature. The Bièvre River in France is the subject of a book of abstract fabric collages, and Les Arbres, a series of six portfolios, mines the symbolic potential of mountains, trees, branches, and leaves in drypoint and watercolor. In 2008, an exhibition of Bourgeois’s work, titled Nature Study, took place in the Royal Botanic Gardens of Scotland, where it was coupled with 19th-century botanical drawings from the Gardens' archive.

Spiders

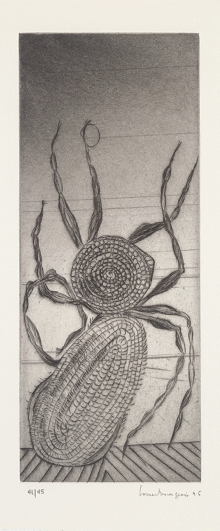

Although recognized for exploring a broad array of materials and motifs, Louise Bourgeois is perhaps best known for sculptures of spiders, ranging in size from a brooch of four inches to monumental outdoor pieces that rise to 30 feet. Long a motif in Symbolist art, the spider encompassed several meanings for Bourgeois, who cited it most frequently as a stand-in for her mother, a tapestry restorer by trade who impressed Bourgeois with her steadfast reliability and clever inventiveness. Yet Bourgeois also appreciated the spider in more general terms, as a protector against evil, pointing out that this crafty arachnid is known for devouring mosquitoes and thereby preventing disease.

Bourgeois’s preoccupation with the spider spans her career, with examples appearing in her drawing and printmaking as early as the late 1940s, but the subject began to have a particular immediacy for her in the mid-1990s. Among the defining projects of that time is Ode à Ma Mère, a 1995 illustrated book comprised of drypoint spiders, along with a text evoking the complicated interpretations Bourgeois framed for them. Bourgeois continued to explore this theme in sculpture, drawing, and printmaking until late in her life. In 2007, she crafted a woven fabric example and also issued a series of digital prints incorporating spiders. That late series, entitled The Fragile, presents her subject in a variety of guises, often merging with a female figure and evoking the aging artist herself.

Words

Writing things down—in diaries, on the backs of drawings, and on countless sheets of paper—served the same function for Louise Bourgeois as making sculpture did; both were used to harness her unpredictable emotions and give them a form outside herself. Keenly sensitive to language and highly articulate, Bourgeois loved dictionaries, where she checked precise meanings and nuance. She interspersed English and French seamlessly in her writings, and also when she spoke.

While writing remained a daily activity for most of Bourgeois’s life, especially during long sleepless nights, the period of the 1950s into the 1960s is remarkable for the voluminous notes she made while undergoing psychoanalysis. While she was suffering from severe depression, her sculptural activity came to a halt but her writing flourished. Over a thousand loose sheets, filled with rhythmic lists of words, phrases, names, and brief texts, make an astounding literary compendium.

In 1992 one of Bourgeois’s parables, She Lost It, became the basis for a performance. She screenprinted the text onto a nearly 200-foot-long banner, in which she wrapped and unwrapped performers outfitted in costumes embroidered with her aphorisms. Her storytelling also appears in illustrated books, none more celebrated than He Disappeared into Complete Silence, of 1947. Many prints demonstrate how she made visual use of words, whether shouting “No” for a protest march, expressing anger at being rejected for an exhibition at the Whitney Museum, or fashioning a sign for what she found difficult to say aloud: “I love you,” “We love you,” “Je t’aime.”

Abstraction

The art of Louise Bourgeois is most closely associated with provocative imagery, in the form of figures, body parts, spiders, and architectural structures. Yet abstraction plays a highly significant role overall. Printed grids, biomorphic ink drawings, and geometric wood totems are found in her early years, organically shaped marble and plaster sculptures come later, and an outpouring of abstract drawings and prints fills her last decade.

For Bourgeois, abstraction was yet another tool for understanding and coping with her feelings, which were always the driving forces of her art. She used terms like “calming,” “caressing,” or “stabbing” to describe strokes, and her drawn lines and evocative shapes reflect shifting moods and perceived vulnerabilities. Her methods harked back to the automatism of the Surrealists, in which compositions evolved intuitively with symbolic overtones. She often took advantage of repetition, drawing simple straight lines across sheets of notepads as she struggled with insomnia, thereby creating a diary of her fraught emotions.

Within the formats of printmaking—books, portfolios, and series—Bourgeois assembled abstract narratives, sometimes adding fragments of text. In fabric, her pages were fashioned from materials with stripes, plaids, or curvilinear patterns. The backdrop of music staves printed on paper provided another abstract foil for her rhythmic lines and shapes. In her last years, Bourgeois took up the technique of soft ground etching, which allowed her wavering touch to be sensitively captured. The result was a series of monumental abstract prints, often with hand-coloring, that are sometimes shown in room-scale installations.

Body Parts

In the 1940s, Louise Bourgeois began an investigation of the partial female nude in a series of paintings, all titled Femme Maison (Woman House), in which houses substitute for heads. These images became feminist icons and subsequently turned up in her sculpture. Later, Bourgeois’s marble works of the 1960s and 1970s were filled with forms resembling breasts, penises, and undulating landscapes, all simultaneously. “Our own body could be considered from a topographical point of view,” she said, “a land with mounds and valleys, and caves and holes.” Latex proved a supple material in which to cast such shapes, culminating in the notorious Fillette (Little Girl), an unmistakable penis, nearly two feet high, hung by a hook from the ceiling.

In the 1970s, Bourgeois exhibited The Destruction of the Father, a claustrophobic, room-size lair crammed with bulbous, erotically charged latex protuberances and scattered animal limbs. She followed up with Confrontation, a stage-like setting accompanied by a performance titled A Banquet/A Fashion Show of Body Parts. She later shifted from merely suggesting body parts to creating more realistic depictions. Her sculptures, drawings, and prints of eyes, ears, hands, and lips all accentuate the functions of the senses, but in their disembodiment also conjure up the eerie Surrealist world of dreams and nightmares. In the 1990s, Bourgeois filled architectural Cells with assemblages of objects, among them marble sculptures of body fragments. Finally, late in life, she created larger-than-life-size stuffed fabric heads, which seem to grimace from the pains of old age.

Figures

The motif of the human figure served as an embodiment of changing moods and desires for Louise Bourgeois throughout her career. Early on, she painted, drew, and printed intimate scenes of family life—her husband reading, her children in the tub, herself setting the table. Her first sculptures, in the late 1940s, were abstracted wood totems that represented people she left behind in France. She called them “personages,” and similar figures appear in her prints of that time.

Later, Bourgeois turned to sculptures of organically shaped body parts that morphed between genders, and from human to landscape forms. She released her aggression in a series of female figures fashioned as weapons, titled Femme Couteau (Knife Woman). By the 1990s, her previously abstracted figural shapes took on a heightened realism. The monumental drypoint Sainte Sébastienne is an explicit representation of the pain she perceived from personal attacks. She said of her artistic strategy, “If I want to express something of immediate, all-consuming importance…I will make a piece that is inspired by a very strong desire to stand in,” for it.

Bourgeois’s repertoire of figures expanded up until her last years, and included recurring images of couples, in all mediums, that reflect a provocative sexuality for which she was well-known. She focused, as well, on the act of giving birth. In prints and drawings, her female figures often display flowing locks that denote both attraction and entrapment and serve as a sign of self-portraiture, since Bourgeois kept her hair very long for most of her life.

Nature

Trees, flowers, nests, mountains, rivers, and clouds are among the elements of nature to which Louise Bourgeois looked for expressions of procreation, growth, and refuge, as well as unsettling states of mind. The natural terrain also became a metaphor for the human body. “It seems rather evident to me,” she said, “that our own body is a figuration that appears in Mother Earth.”

While growing up, Bourgeois and her siblings each had a garden plot where they planted roses and geraniums and tended to apple and pear trees. Later she explored the workings of nature with her own children at their country house in Easton, Connecticut. This preoccupation with the natural world shows itself in her work at various intervals, particularly in the 1960s, when she fashioned cocoons and lairs of plaster, and bulbous landscapes of marble, latex, and hardened plastics. This turn to mutable, biomorphic forms was in stark contrast to the rigid wood figures she created in the 1940s and 1950s, or the architectural structures that became her Cells series in later years.

Bourgeois’s prints, drawings, and illustrated books of the 1990s and 2000s are filled with references to nature. The Bièvre River in France is the subject of a book of abstract fabric collages, and Les Arbres, a series of six portfolios, mines the symbolic potential of mountains, trees, branches, and leaves in drypoint and watercolor. In 2008, an exhibition of Bourgeois’s work, titled Nature Study, took place in the Royal Botanic Gardens of Scotland, where it was coupled with 19th-century botanical drawings from the Gardens' archive.

Spirals

Within Louise Bourgeois’s overall investigation of abstract motifs, the spiral holds a distinct place, recurring across her oeuvre. It is found in segmented wood sculptures of the early 1950s that twist and turn, in a plaster mound from the 1960s that suggests a tomb monument, and in a bronze figure of the 1980s that struggles inside a cocoon and hangs precariously from the ceiling by a string. Numerous drawings and prints add to this evocative repertoire. In the 1990s, Bourgeois even created a performance piece, She Lost It, in which she wrapped and unwrapped her performers in a spiraling gauze banner, nearly 200 feet long, printed with one of her parables.

To describe the symbolic resonance spirals held for her, Bourgeois harked back to her childhood, when she watched the workers in her family’s tapestry restoration business wash tapestries in the river and then fiercely wring them out. She segued easily from this recollection to the fantasy of wringing the neck of someone she despised. But in fact, the spiral functioned as a visual metaphor for a range of her emotions, not just anger.

Bourgeois stressed the spiral’s two opposing directions: inward and outward. The outward movement represented “giving, and giving up control, trust and positive energy….” While the winding in of the spiral embodied “a tightening, a retreating, a compacting to the point of disappearance.” She said, “You can get twisted and strangled by your emotions.” Always reflecting her volatile temperament, Bourgeois’s spirals are endlessly variable—as coils of tension, protective cocoons, and even entrapping spider webs.

Animals & Insects

Creatures of the natural world were a source of fascination to Bourgeois from the time her father populated the family property with an assortment of hens, dogs, ducks, rabbits, pigs, and even a donkey, all meant to live in harmony. When she raised her own small boys, they spent time together observing nature at their weekend house in Easton, Connecticut, and also had family pets—cats named Tyger and Champfleurette, who appeared in Bourgeois’s dreams. Always attempting to decipher her own behavior and relationships, she looked to animals and insects for qualities they might share with humans.

Some of Bourgeois’s early paintings show plants and animals, and living things are also implied in the nests and lairs she shaped from plaster in the 1960s. Later works include fierce depictions of a flayed Rabbit in 1970, and a monstrous half-dog, half-mythic female titled She-Fox, in 1985. Such motifs appear only occasionally in her sculpture but take a distinctive place within her more intimate prints and drawings, where one finds a bestiary of cows, horses, pigs, cats, mosquitoes, and even an exotic llama. Spiders—actually classified as arachnids—form a separate category.

The artist anthropomorphizes this subject matter, particularly the wily cat. She invents a feline Self Portrait with five legs to help maintain stability. Champfleurette, the family pet, becomes a beguiling temptress who sports high-heels. Even Mosquito, the insect she dreaded as a summer pest, is seen with radiating locks, breasts, and a fetus.

Fabric Works

Louise Bourgeois’s connection to fabric goes back to her childhood years when she helped out in her family’s tapestry restoration workshop. As an adult, she long associated the act of sewing with repairing on a symbolic level, as she attempted to fix the damage she caused in personal relationships. She even held a special regard for spools of thread and needles as tools that served this purpose.

Fabric took center stage as a sculptural element in Bourgeois’s work in the 1990s, as she began to mine material from clothes accumulated over a lifetime. She hung old dresses, slips, and nightwear in installations, and then manipulated timeworn terry cloth into nearly life-size figures or eerie portrait-like heads. In 1999, she hired a seamstress, Mercedes Katz, to help with this work and set her up in a workshop-like area on the lower level of her house, where she also installed two small printing presses. By 2000, Bourgeois had turned to printing on old handkerchiefs, and then other fabrics. She also constructed books of fabric collages.

Printing on fabric was a major preoccupation of Bourgeois’s later years and she highly valued her collaboration with Katz and the various printers with whom she worked. The old fabrics she selected resonated with memories yet, on occasion, she ran out of material when making an edition and had to seek out matching fabrics. To this same end, she sometimes took advantage of digital possibilities for duplicating aging or fading effects. In contrast to her prints and books on paper, Bourgeois’s fabric works have a tactile presence that gives them a decidedly sculptural dimension.

Motherhood & Family

Among Louise Bourgeois’s most symbolic titles is One and Others, referring to a preoccupation with personal relationships that motivated much of her art. She constantly struggled with a need for attachments, yet she experienced difficulty and ambivalence when dealing with those around her, most significantly her parents, siblings, husband, and children. Her memories of her mother and father never dimmed and found expression in countless works, as significant as the spiders that represented her meticulous mother, or the room-size tableau, The Destruction of the Father, that evokes violence and anger.

Upon the births of her own children, Bourgeois felt a profound sense of gratitude but was overwhelmed by feelings of inadequacy. “There I was,” she said, “a wife and mother, and I was afraid of my family…afraid not to measure up.” She relived the birth experience in her art time and again—her own birth and that of her children—never more so than in the last decade of her life. Among her representations is a mother with an umbilical cord that remains attached to a baby.

Bourgeois also recalled simple family life of the 1940s, when her children were young, reinterpreting drawings of that period in new printed images. For her, it was as if no time had passed when she created an aquatint and drypoint in the 1990s depicting two of her small boys in the tub. Similarly, she assembled the illustrated book Album in 1994, gathering together nearly 70 snapshots from her long-ago childhood that encapsulated that earlier time.

Objects

Transformation is at the core of Bourgeois’s treatment of objects as artistic motifs. In her very early prints, chairs, tables, clocks, bathtubs, and storage cabinets take on amplified meanings as they loom large in her depicted world and share space with family members. In the later 1940s and 1950s, she shifted to figural presences, which would dominate her sculpture.

Her practice of imbuing common objects with symbolic functions becomes palpable in sculptures of the late 1960s, like the fierce marble Femme Couteau, in which a woman turns herself into a knife, or the equally threatening bronze object Molotov Cocktail, a vivid reference to the rioters of the era. For Bourgeois, “Symbols are indispensable...these things are very, very clear, very simple—and absolutely devastating.”

Bourgeois filled her Cells of the 1990s and 2000s with a variety of everyday objects gathered from her house or studio, most saved for many years. She carefully placed perfume bottles, spools of thread, mirrors, lanterns, and old furnishings like tables, chairs, stools, and beds in close proximity to her sculptural works, giving all these objects added resonance. They are further transformed by the contexts of these strange room-like structures. In later prints and drawings, Bourgeois gave objects anthropomorphic qualities. Scissors are seen giving birth to baby scissors in one drypoint and aquatint, and an eroticized bed is the primary subject of a large group of printed compositions. Bourgeois described beds as “erotic objects…where you lie with your husband, where your children were born and you will die.”

Words

Writing things down—in diaries, on the backs of drawings, and on countless sheets of paper—served the same function for Louise Bourgeois as making sculpture did; both were used to harness her unpredictable emotions and give them a form outside herself. Keenly sensitive to language and highly articulate, Bourgeois loved dictionaries, where she checked precise meanings and nuance. She interspersed English and French seamlessly in her writings, and also when she spoke.

While writing remained a daily activity for most of Bourgeois’s life, especially during long sleepless nights, the period of the 1950s into the 1960s is remarkable for the voluminous notes she made while undergoing psychoanalysis. While she was suffering from severe depression, her sculptural activity came to a halt but her writing flourished. Over a thousand loose sheets, filled with rhythmic lists of words, phrases, names, and brief texts, make an astounding literary compendium.

In 1992 one of Bourgeois’s parables, She Lost It, became the basis for a performance. She screenprinted the text onto a nearly 200-foot-long banner, in which she wrapped and unwrapped performers outfitted in costumes embroidered with her aphorisms. Her storytelling also appears in illustrated books, none more celebrated than He Disappeared into Complete Silence, of 1947. Many prints demonstrate how she made visual use of words, whether shouting “No” for a protest march, expressing anger at being rejected for an exhibition at the Whitney Museum, or fashioning a sign for what she found difficult to say aloud: “I love you,” “We love you,” “Je t’aime.”

Architecture

The architecture of New York City had an immediate impact on Louise Bourgeois when she arrived from France in 1938, newly married to American art historian Robert Goldwater. Her first print, a holiday greeting card for that year, shows fragments of both her new home and the Paris she left behind. New York’s skyscrapers also underlie the visual narratives that unfold in her celebrated illustrated book He Disappeared into Complete Silence, of 1947. She said, “My skyscrapers reflect a human condition,” and here they became personifications of loneliness, alienation, anger, and hostility. At that time, Bourgeois also created her Femme Maison, depicting a female body topped by a house. It became a feminist icon and was later issued as a print.

The architectural forms in Bourgeois’s early paintings and prints evolved into totem-like wood figures for her sculptural debut in the late 1940s. Dwellings of one form or another became ongoing motifs—from organically shaped plaster lairs in the 1960s to room-scale enclosures called Cells that dominated the later years. All these works are sites of personal dramas, where Bourgeois gave symbolic form to her vivid memories and powerful emotions. She even meticulously re-created particular buildings in marble—for example, her childhood home in Choisy-le-Roi, France, and New York’s Institute of Fine Arts, where her husband worked—placing them in assembled environments. For Bourgeois, who had initially trained in mathematics, architecture offered order, structure, and stability for tumultuous states of mind.

Faces & Portaits

A “drama of the self” is how Louise Bourgeois once described a work, perceiving her art overall as a form of self-portraiture. The characters in this drama occasionally included family members, most memorably her mother who appears as a spider. But, most often, it was her own emotions that Bourgeois transformed into “portraits.” She became the threatening Femme Couteau (Knife Woman), the stifled Femme Maison (Woman House), or the flirtatious Femme Volage (Fickle Woman). Bourgeois also showed herself in various configurations as The Bad Mother. In Bosom Lady, of 1948, she observed that three eggs in a bowl near a bird-woman are her “jewels”—her three children. But she also pointed out that this figure could easily “escape by flight.”

Bourgeois revealed her fears, anger, and despair most vividly in depictions of the human face. She called these “portraits of a mood,” and painful emotions are often communicated through contorted expressions or dizzying eyes. Very long hair—a pride of Bourgeois’s for most of her life—became a symbol of sexuality that could represent seduction, entanglement, or vulnerability. In the early 2000s, in a powerful expression of old age, Bourgeois created a series of fabric sculptures of heads that seem to cry out or grimace in pain. Then, in her last year, she issued Self Portrait, a series of 24 drypoints on fabric portraying various interpretations of her life from birth to adulthood. She also sewed these prints in a clock shape on a single piece of fabric, clearly evoking the passage of time.

Music

Children’s songs, piano lessons, and records were intimate memories of growing up for Louise Bourgeois. In a diary entry from 1950 she listed old family recordings she came across in the attic—mostly operas, but also popular French songs of the day. Later, in old age, music was a comfort. Listening to it at night calmed her during bouts of insomnia, and she found humming or singing songs from the past to be soothing.

For Bourgeois, musical rhythms provided reliability, something she deeply appreciated but found elusive in herself. She relished her metronome and kept it close by on her work desk, among her pens, pencils, brushes, and paper. The voluminous notes she wrote in diaries and on the backs of drawings often contain words that read like free-associative lyrics: “…rain, water can, water tap, kettle, moss, splash, waddle, puddle, mud pies, muddle, drip, leak, pump, dry well….” Other handwritten lists hint at her musical tastes: “Mozart, La Flute enchantée, Buddy Holly, Houston Texas yodels, Rolling Stones, Chuck Berry, Hardbreak Hotel, I Get So Lonely I Could Die.”

Printed music paper became a major element in Bourgeois’s work in the mid-1990s, with a series called The Insomnia Drawings. The horizontal staves provided a visual rhythm and also a foil against which to react. They form the backdrop for her Fugue portfolio of 2002–05, where squares, circles, lines, and spirals suggest reverberating sounds. Also during these late years, Bourgeois issued two CDs capturing her own brand of singing and inventive lyrics.

Spiders

Although recognized for exploring a broad array of materials and motifs, Louise Bourgeois is perhaps best known for sculptures of spiders, ranging in size from a brooch of four inches to monumental outdoor pieces that rise to 30 feet. Long a motif in Symbolist art, the spider encompassed several meanings for Bourgeois, who cited it most frequently as a stand-in for her mother, a tapestry restorer by trade who impressed Bourgeois with her steadfast reliability and clever inventiveness. Yet Bourgeois also appreciated the spider in more general terms, as a protector against evil, pointing out that this crafty arachnid is known for devouring mosquitoes and thereby preventing disease.

Bourgeois’s preoccupation with the spider spans her career, with examples appearing in her drawing and printmaking as early as the late 1940s, but the subject began to have a particular immediacy for her in the mid-1990s. Among the defining projects of that time is Ode à Ma Mère, a 1995 illustrated book comprised of drypoint spiders, along with a text evoking the complicated interpretations Bourgeois framed for them. Bourgeois continued to explore this theme in sculpture, drawing, and printmaking until late in her life. In 2007, she crafted a woven fabric example and also issued a series of digital prints incorporating spiders. That late series, entitled The Fragile, presents her subject in a variety of guises, often merging with a female figure and evoking the aging artist herself.