Bourgeois began making prints in the late 1930s, first experimenting at home with relief techniques, and then learning lithography at the Art Students League. She practiced intaglio techniques, which she preferred, at Stanley William Hayter’s Atelier 17, and also bought her own small press. When she turned to sculpture later in the 1940s, Bourgeois abandoned printmaking, taking it up again only in the late 1980s, when it then became integral to her work.

“There is no rivalry.... They say the same things in different ways.”

Aquatint

The aquatint technique, which has effects resembling watercolor, is usually undertaken in a print workshop where specialized materials and equipment are available. However, some of Bourgeois’s notes from the 1940s indicate that she studied the necessary steps and succeeded in making a few aquatints at home. Later, after the resurgence of her printmaking in the 1990s, Bourgeois depended on the expertise of a professional printer, such as Felix Harlan of Harlan & Weaver, when she wanted to incorporate aquatint. She might choose the technique if her source drawing included watercolor or other tonal areas. On the other hand, she also liked to simply add watercolor directly to her prints, since that method gave her the most control.

Generally, Bourgeois shied away from complex printmaking techniques and preferred more direct ways of working. Also, she had a certain fear of acid, which is required in aquatint. She avoided using acid herself and did not take advantage of the assistance that would have been provided at a print workshop. Temperamentally, she was not suited to the workshop environment and this was especially evident in her later years. She felt most comfortable when printers came to her house to collaborate, and she especially liked to take advantage of the small printing presses she kept on the lower level.

Digital

Bourgeois turned to digital technologies for printmaking when her 2002 fabric book, Ode à l’Oubli, was editioned. Judith Solodkin of SOLO Impression, a longtime friend of Bourgeois’s, was called upon to determine the means of duplicating that unique volume, which is filled with sewn collages of varying materials and patterns. Solodkin incorporated lithography, embroidery, appliqué, and various kinds of sewing, but also sought out the textile printing expertise of Raylene Marasco, of Dyenamix. Through digital printing and archival dyes, Marasco recreated the patterns and textures of Bourgeois’s old and worn fabrics. The artist was extremely pleased with the results.

Bourgeois then made use of digital printing at Dyenamix for many of her late projects on fabric, which became her preferred support for prints. Such projects include Do Not Abandon Me (2009–10), a series in collaboration with British artist Tracey Emin, and To Whom It May Concern (2010), an illustrated book with poet Gary Indiana, both of which replicate the effects of gouache through digital means.

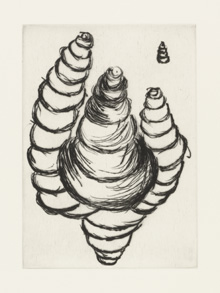

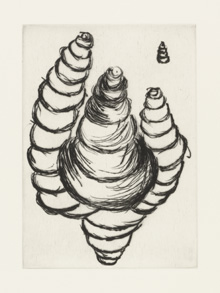

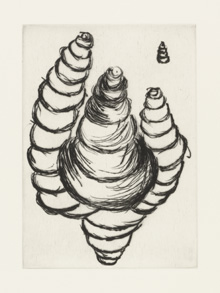

Drypoint

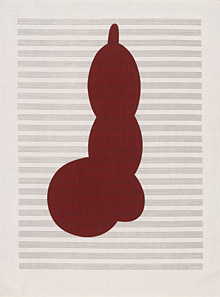

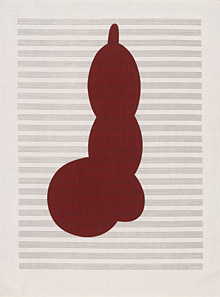

Bourgeois employed drypoint more frequently than any other technique by far, creating some 1,500 prints that make sole use of it, or adding it to combinations of other intaglio techniques. She liked the fact that the drypoint needle was easy to manipulate and that no acid or special equipment was required. She referred to the scratching as an “endearing” gesture, a kind of “stroking.” While it could not “convert antagonism,” something she admired in engraving, she liked the immediacy of drypoint’s effects, with its soft, irregular line and tentative qualities.

Bourgeois made drypoints in the 1940s, working at home, and took up the technique again when she returned to printmaking in the late 1980s, most often working with printer Felix Harlan of Harlan & Weaver. She chose it for some her most iconic print projects, such as the Sainte Sébastienne series, which led to a monumental print nearly 40 inches high, the portfolio Anatomy, with its catalog of body parts, and the illustrated book Ode à Ma Mère, which presents a range of her celebrated spider imagery.

Engraving

Bourgeois had a reverence for what she called the “symbolic power” of engraving, often referring to its ability to “convert aggression” into something useful. But she bemoaned the fact that strength and control were required to push the burin through the metal plate. She complained that she did not have the necessary “biceps.” However, she loved the stiff, assertive, tactile quality of the engraved line.

Bourgeois began making engravings in the 1940s at Atelier 17, the print workshop Stanley William Hayter temporarily transferred from Paris to New York during the war years. Though she did not usually respond favorably to a workshop environment, Bourgeois gravitated to Atelier 17 for the company of the international group of artists who frequented it. Bourgeois found Hayter intimidating as he demonstrated engraving, but remembered feeling useful in the shop because she could facilitate communication with the artists who spoke only French. For her most ambitious print project at that time—the illustrated book He Disappeared into Complete Silence—Bourgeois turned to engraving. She employed it again for the second edition, published years later in 2005, when she worked with printer Felix Harlan of Harlan & Weaver. She also chose engraving for the large-scale illustrated book the puritan, published in 1990 with Osiris.

Etching

Bourgeois made use of hard ground etching relatively infrequently. Its fluid linearity appealed to her less than the more irregular effects of drypoint. Also, she preferred to stay away from acid, which is needed for incising etched lines into metal plates once they are drawn. In the 1940s, Bourgeois employed etching only on occasion. In the late 1980s, she was encouraged to take it up again by publisher Ben Shiff of Osiris and made a number of prints in the technique, working with Wingate Studio in Hinsdale, NH.

In her early period of printmaking, Bourgeois worked also in soft ground etching, a technique that usually involves drawing compositions on paper laid over plates covered in a waxy ground. Soft ground can capture the subtle qualities of pencil or crayon lines and, in the last decade of her life, again working with Shiff, Bourgeois took advantage of its potential for a major series of works, printed with Wingate Studio. The publisher supplied her with long narrow plates that fit her work table, and she worked on them easily with her drawing tools. Some of the soft ground etchings that resulted were editioned; others became the basis of unique works with hand additions and, sometimes, collage elements.

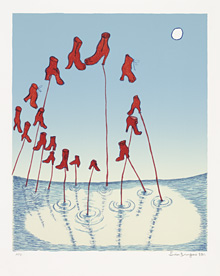

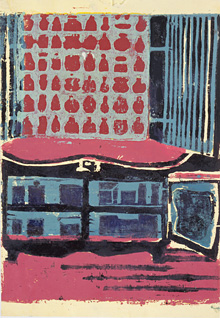

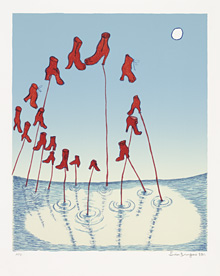

Lithography

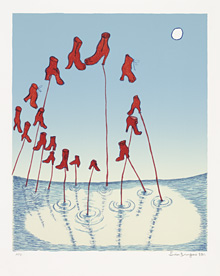

It is usually painters who are attracted to lithography, since marking the flat surface of a lithographic stone or plate most closely approximates painting. Bourgeois actually had no natural inclination for this technique, and when master lithographer Judith Solodkin of SOLO Impression brought two printing stones to Bourgeois’s house in the late 1980s, she did not respond with much enthusiasm. Bourgeois was already familiar with lithography, having learned it at the Art Students League in the early 1940s under the tutelage of artist Will Barnet. She made several examples at that time, during a period when she was a painter and had not yet turned definitively to sculpture.

Bourgeois’s friendship with Solodkin was probably the reason she pursued lithography later in her career, and she eventually made a considerable group of significant prints in the medium. She responded especially to the vibrant color effects possible with this technique, and particularly its ability to produce bright blues and reds. She also liked the fact that large editions could be made easily, and often chose lithography for benefit prints.

Other Techniques

In addition to traditional printmaking techniques and newer digital processes, Bourgeois occasionally turned to other means for her printed and editioned works. She sometimes availed herself of photocopy, for example, or other mechanical copying techniques, as she determined the ultimate form of a composition. She might make photocopies in various sizes before deciding on final dimensions, or create a photocopy or a tracing to mark up with new ideas, or to aid in the process of transferring drawings onto printing plates. As certain compositions evolved, she sporadically employed monotype as a way to test out a tonal effect, or to obliterate earlier drawn elements. She also might utilize an unusual fabric technique, like weaving, or experiment with Mixografia®, which intrigued her with its possibilities for producing textures on paper. Transforming fabric collages into book pages is yet another example of the ways she worked outside the realm of traditional techniques.

Bourgeois also made a group of works known as “multiples,” which are small-scale sculptural objects fabricated in relatively large editions. In these instances, her choice of materials varied and included rubber, latex, marble, bronze, or whatever else suited her purpose. Since such works are often produced by the same firms that publish prints, they are often documented with an artist’s printmaking, as they are here for Bourgeois’s work.

Photogravure

Photogravure is employed primarily for transferring images onto printing plates, and Bourgeois occasionally used it for this purpose. Her first opportunity came in the mid-1980s, when she met printer Deli Sacilotto, a specialist in the technique. This was just before she returned to printmaking in a sustained fashion, and she made photogravures of existing drawings in response to several requests for works to benefit causes. She then varied the editions with colored inks and papers.

Bourgeois’s most concerted effort with photogravure arose from her desire to complete the edition of He Disappeared into Complete Silence, an illustrated book she had begun in the 1940s. She was distressed that she lost the engraved printing plates—since she routinely saved everything—and had the idea of making photogravure plates to replicate them, with Sacilotto’s assistance. This project did not get very far. She also attempted to reproduce the plates in engraving, with printer Christian Guérin. Ultimately a second edition of the book was completed in 2005, working with Harlan & Weaver, and the initial transfer of images was accomplished in photogravure, with Renaissance Press of Ashuelot, NH.

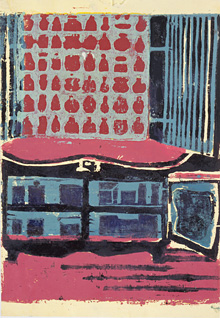

Relief

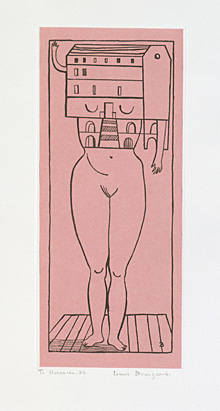

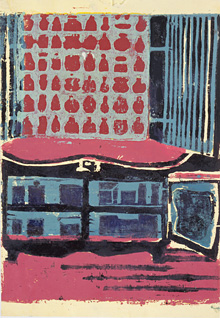

Bourgeois made a relatively small number of relief prints, which is surprising given that the cutting and gouging inherent to the process might make them a natural choice for a sculptor. When she took up printmaking in the late 1930s, Bourgeois began with woodcut and linoleum cut, on which she experimented at home without the need for specialized equipment. Her early attempts are ambitious in their use of multiple colors, each requiring a separate block. Bourgeois later said she did not actually like the traces of wood grain that are often the distinctive and sought-after element of woodcuts.

Bourgeois also made isolated examples of stamped prints, and rubbings from surfaces she carved—both relief processes—but she never turned her attention fully to these techniques. Examples of relief prints from late in her career were the result of others suggesting she try the techniques for translating particular imagery from drawings. By this time Bourgeois was working with professional printers, and they often piqued her curiosity about the potential effects of one medium or another.

Screenprint

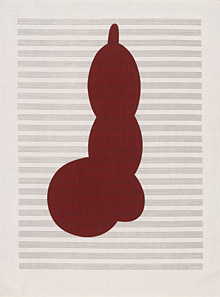

The technique of screenprint is usually selected for its bold and assertive flat surfaces. While these were not effects Bourgeois usually sought in her printmaking, she was attracted to the technique through the suggestion of printers with whom she worked. David Procuniar, of Procuniar Workshop, is a specialist she came to know as an artist who regularly frequented the Sunday salons she held at her home. Bourgeois ultimately worked with Procuniar on several ambitious screenprint projects, in which her drawings were translated with a level of vibrancy that she liked very much.

Bourgeois also turned to screenprint for its ability to print easily on fabric, which was the support she favored in her last years. In addition to her work with Procuniar, she depended on the expertise of Raylene Marasco of Dyenamix, a firm specializing in textile printing. Marasco occasionally printed images for Bourgeois in both screenprint and digital techniques in order to show her varying possibilities; from time to time, she selected the more vivid effects of screenprint.

Aquatint

The aquatint technique, which has effects resembling watercolor, is usually undertaken in a print workshop where specialized materials and equipment are available. However, some of Bourgeois’s notes from the 1940s indicate that she studied the necessary steps and succeeded in making a few aquatints at home. Later, after the resurgence of her printmaking in the 1990s, Bourgeois depended on the expertise of a professional printer, such as Felix Harlan of Harlan & Weaver, when she wanted to incorporate aquatint. She might choose the technique if her source drawing included watercolor or other tonal areas. On the other hand, she also liked to simply add watercolor directly to her prints, since that method gave her the most control.

Generally, Bourgeois shied away from complex printmaking techniques and preferred more direct ways of working. Also, she had a certain fear of acid, which is required in aquatint. She avoided using acid herself and did not take advantage of the assistance that would have been provided at a print workshop. Temperamentally, she was not suited to the workshop environment and this was especially evident in her later years. She felt most comfortable when printers came to her house to collaborate, and she especially liked to take advantage of the small printing presses she kept on the lower level.

Drypoint

Bourgeois employed drypoint more frequently than any other technique by far, creating some 1,500 prints that make sole use of it, or adding it to combinations of other intaglio techniques. She liked the fact that the drypoint needle was easy to manipulate and that no acid or special equipment was required. She referred to the scratching as an “endearing” gesture, a kind of “stroking.” While it could not “convert antagonism,” something she admired in engraving, she liked the immediacy of drypoint’s effects, with its soft, irregular line and tentative qualities.

Bourgeois made drypoints in the 1940s, working at home, and took up the technique again when she returned to printmaking in the late 1980s, most often working with printer Felix Harlan of Harlan & Weaver. She chose it for some her most iconic print projects, such as the Sainte Sébastienne series, which led to a monumental print nearly 40 inches high, the portfolio Anatomy, with its catalog of body parts, and the illustrated book Ode à Ma Mère, which presents a range of her celebrated spider imagery.

Etching

Bourgeois made use of hard ground etching relatively infrequently. Its fluid linearity appealed to her less than the more irregular effects of drypoint. Also, she preferred to stay away from acid, which is needed for incising etched lines into metal plates once they are drawn. In the 1940s, Bourgeois employed etching only on occasion. In the late 1980s, she was encouraged to take it up again by publisher Ben Shiff of Osiris and made a number of prints in the technique, working with Wingate Studio in Hinsdale, NH.

In her early period of printmaking, Bourgeois worked also in soft ground etching, a technique that usually involves drawing compositions on paper laid over plates covered in a waxy ground. Soft ground can capture the subtle qualities of pencil or crayon lines and, in the last decade of her life, again working with Shiff, Bourgeois took advantage of its potential for a major series of works, printed with Wingate Studio. The publisher supplied her with long narrow plates that fit her work table, and she worked on them easily with her drawing tools. Some of the soft ground etchings that resulted were editioned; others became the basis of unique works with hand additions and, sometimes, collage elements.

Other Techniques

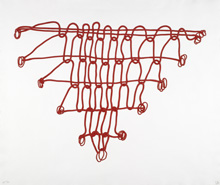

In addition to traditional printmaking techniques and newer digital processes, Bourgeois occasionally turned to other means for her printed and editioned works. She sometimes availed herself of photocopy, for example, or other mechanical copying techniques, as she determined the ultimate form of a composition. She might make photocopies in various sizes before deciding on final dimensions, or create a photocopy or a tracing to mark up with new ideas, or to aid in the process of transferring drawings onto printing plates. As certain compositions evolved, she sporadically employed monotype as a way to test out a tonal effect, or to obliterate earlier drawn elements. She also might utilize an unusual fabric technique, like weaving, or experiment with Mixografia®, which intrigued her with its possibilities for producing textures on paper. Transforming fabric collages into book pages is yet another example of the ways she worked outside the realm of traditional techniques.

Bourgeois also made a group of works known as “multiples,” which are small-scale sculptural objects fabricated in relatively large editions. In these instances, her choice of materials varied and included rubber, latex, marble, bronze, or whatever else suited her purpose. Since such works are often produced by the same firms that publish prints, they are often documented with an artist’s printmaking, as they are here for Bourgeois’s work.

Relief

Bourgeois made a relatively small number of relief prints, which is surprising given that the cutting and gouging inherent to the process might make them a natural choice for a sculptor. When she took up printmaking in the late 1930s, Bourgeois began with woodcut and linoleum cut, on which she experimented at home without the need for specialized equipment. Her early attempts are ambitious in their use of multiple colors, each requiring a separate block. Bourgeois later said she did not actually like the traces of wood grain that are often the distinctive and sought-after element of woodcuts.

Bourgeois also made isolated examples of stamped prints, and rubbings from surfaces she carved—both relief processes—but she never turned her attention fully to these techniques. Examples of relief prints from late in her career were the result of others suggesting she try the techniques for translating particular imagery from drawings. By this time Bourgeois was working with professional printers, and they often piqued her curiosity about the potential effects of one medium or another.

Digital

Bourgeois turned to digital technologies for printmaking when her 2002 fabric book, Ode à l’Oubli, was editioned. Judith Solodkin of SOLO Impression, a longtime friend of Bourgeois’s, was called upon to determine the means of duplicating that unique volume, which is filled with sewn collages of varying materials and patterns. Solodkin incorporated lithography, embroidery, appliqué, and various kinds of sewing, but also sought out the textile printing expertise of Raylene Marasco, of Dyenamix. Through digital printing and archival dyes, Marasco recreated the patterns and textures of Bourgeois’s old and worn fabrics. The artist was extremely pleased with the results.

Bourgeois then made use of digital printing at Dyenamix for many of her late projects on fabric, which became her preferred support for prints. Such projects include Do Not Abandon Me (2009–10), a series in collaboration with British artist Tracey Emin, and To Whom It May Concern (2010), an illustrated book with poet Gary Indiana, both of which replicate the effects of gouache through digital means.

Engraving

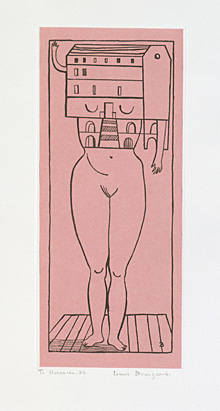

Bourgeois had a reverence for what she called the “symbolic power” of engraving, often referring to its ability to “convert aggression” into something useful. But she bemoaned the fact that strength and control were required to push the burin through the metal plate. She complained that she did not have the necessary “biceps.” However, she loved the stiff, assertive, tactile quality of the engraved line.

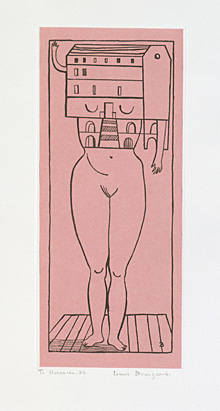

Bourgeois began making engravings in the 1940s at Atelier 17, the print workshop Stanley William Hayter temporarily transferred from Paris to New York during the war years. Though she did not usually respond favorably to a workshop environment, Bourgeois gravitated to Atelier 17 for the company of the international group of artists who frequented it. Bourgeois found Hayter intimidating as he demonstrated engraving, but remembered feeling useful in the shop because she could facilitate communication with the artists who spoke only French. For her most ambitious print project at that time—the illustrated book He Disappeared into Complete Silence—Bourgeois turned to engraving. She employed it again for the second edition, published years later in 2005, when she worked with printer Felix Harlan of Harlan & Weaver. She also chose engraving for the large-scale illustrated book the puritan, published in 1990 with Osiris.

Lithography

It is usually painters who are attracted to lithography, since marking the flat surface of a lithographic stone or plate most closely approximates painting. Bourgeois actually had no natural inclination for this technique, and when master lithographer Judith Solodkin of SOLO Impression brought two printing stones to Bourgeois’s house in the late 1980s, she did not respond with much enthusiasm. Bourgeois was already familiar with lithography, having learned it at the Art Students League in the early 1940s under the tutelage of artist Will Barnet. She made several examples at that time, during a period when she was a painter and had not yet turned definitively to sculpture.

Bourgeois’s friendship with Solodkin was probably the reason she pursued lithography later in her career, and she eventually made a considerable group of significant prints in the medium. She responded especially to the vibrant color effects possible with this technique, and particularly its ability to produce bright blues and reds. She also liked the fact that large editions could be made easily, and often chose lithography for benefit prints.

Photogravure

Photogravure is employed primarily for transferring images onto printing plates, and Bourgeois occasionally used it for this purpose. Her first opportunity came in the mid-1980s, when she met printer Deli Sacilotto, a specialist in the technique. This was just before she returned to printmaking in a sustained fashion, and she made photogravures of existing drawings in response to several requests for works to benefit causes. She then varied the editions with colored inks and papers.

Bourgeois’s most concerted effort with photogravure arose from her desire to complete the edition of He Disappeared into Complete Silence, an illustrated book she had begun in the 1940s. She was distressed that she lost the engraved printing plates—since she routinely saved everything—and had the idea of making photogravure plates to replicate them, with Sacilotto’s assistance. This project did not get very far. She also attempted to reproduce the plates in engraving, with printer Christian Guérin. Ultimately a second edition of the book was completed in 2005, working with Harlan & Weaver, and the initial transfer of images was accomplished in photogravure, with Renaissance Press of Ashuelot, NH.

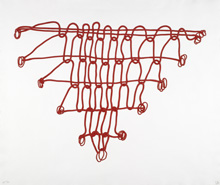

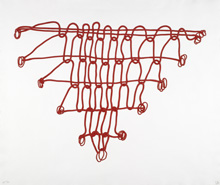

Screenprint

The technique of screenprint is usually selected for its bold and assertive flat surfaces. While these were not effects Bourgeois usually sought in her printmaking, she was attracted to the technique through the suggestion of printers with whom she worked. David Procuniar, of Procuniar Workshop, is a specialist she came to know as an artist who regularly frequented the Sunday salons she held at her home. Bourgeois ultimately worked with Procuniar on several ambitious screenprint projects, in which her drawings were translated with a level of vibrancy that she liked very much.

Bourgeois also turned to screenprint for its ability to print easily on fabric, which was the support she favored in her last years. In addition to her work with Procuniar, she depended on the expertise of Raylene Marasco of Dyenamix, a firm specializing in textile printing. Marasco occasionally printed images for Bourgeois in both screenprint and digital techniques in order to show her varying possibilities; from time to time, she selected the more vivid effects of screenprint.

Aquatint

The aquatint technique, which has effects resembling watercolor, is usually undertaken in a print workshop where specialized materials and equipment are available. However, some of Bourgeois’s notes from the 1940s indicate that she studied the necessary steps and succeeded in making a few aquatints at home. Later, after the resurgence of her printmaking in the 1990s, Bourgeois depended on the expertise of a professional printer, such as Felix Harlan of Harlan & Weaver, when she wanted to incorporate aquatint. She might choose the technique if her source drawing included watercolor or other tonal areas. On the other hand, she also liked to simply add watercolor directly to her prints, since that method gave her the most control.

Generally, Bourgeois shied away from complex printmaking techniques and preferred more direct ways of working. Also, she had a certain fear of acid, which is required in aquatint. She avoided using acid herself and did not take advantage of the assistance that would have been provided at a print workshop. Temperamentally, she was not suited to the workshop environment and this was especially evident in her later years. She felt most comfortable when printers came to her house to collaborate, and she especially liked to take advantage of the small printing presses she kept on the lower level.

Engraving

Bourgeois had a reverence for what she called the “symbolic power” of engraving, often referring to its ability to “convert aggression” into something useful. But she bemoaned the fact that strength and control were required to push the burin through the metal plate. She complained that she did not have the necessary “biceps.” However, she loved the stiff, assertive, tactile quality of the engraved line.

Bourgeois began making engravings in the 1940s at Atelier 17, the print workshop Stanley William Hayter temporarily transferred from Paris to New York during the war years. Though she did not usually respond favorably to a workshop environment, Bourgeois gravitated to Atelier 17 for the company of the international group of artists who frequented it. Bourgeois found Hayter intimidating as he demonstrated engraving, but remembered feeling useful in the shop because she could facilitate communication with the artists who spoke only French. For her most ambitious print project at that time—the illustrated book He Disappeared into Complete Silence—Bourgeois turned to engraving. She employed it again for the second edition, published years later in 2005, when she worked with printer Felix Harlan of Harlan & Weaver. She also chose engraving for the large-scale illustrated book the puritan, published in 1990 with Osiris.

Other Techniques

In addition to traditional printmaking techniques and newer digital processes, Bourgeois occasionally turned to other means for her printed and editioned works. She sometimes availed herself of photocopy, for example, or other mechanical copying techniques, as she determined the ultimate form of a composition. She might make photocopies in various sizes before deciding on final dimensions, or create a photocopy or a tracing to mark up with new ideas, or to aid in the process of transferring drawings onto printing plates. As certain compositions evolved, she sporadically employed monotype as a way to test out a tonal effect, or to obliterate earlier drawn elements. She also might utilize an unusual fabric technique, like weaving, or experiment with Mixografia®, which intrigued her with its possibilities for producing textures on paper. Transforming fabric collages into book pages is yet another example of the ways she worked outside the realm of traditional techniques.

Bourgeois also made a group of works known as “multiples,” which are small-scale sculptural objects fabricated in relatively large editions. In these instances, her choice of materials varied and included rubber, latex, marble, bronze, or whatever else suited her purpose. Since such works are often produced by the same firms that publish prints, they are often documented with an artist’s printmaking, as they are here for Bourgeois’s work.

Screenprint

The technique of screenprint is usually selected for its bold and assertive flat surfaces. While these were not effects Bourgeois usually sought in her printmaking, she was attracted to the technique through the suggestion of printers with whom she worked. David Procuniar, of Procuniar Workshop, is a specialist she came to know as an artist who regularly frequented the Sunday salons she held at her home. Bourgeois ultimately worked with Procuniar on several ambitious screenprint projects, in which her drawings were translated with a level of vibrancy that she liked very much.

Bourgeois also turned to screenprint for its ability to print easily on fabric, which was the support she favored in her last years. In addition to her work with Procuniar, she depended on the expertise of Raylene Marasco of Dyenamix, a firm specializing in textile printing. Marasco occasionally printed images for Bourgeois in both screenprint and digital techniques in order to show her varying possibilities; from time to time, she selected the more vivid effects of screenprint.

Digital

Bourgeois turned to digital technologies for printmaking when her 2002 fabric book, Ode à l’Oubli, was editioned. Judith Solodkin of SOLO Impression, a longtime friend of Bourgeois’s, was called upon to determine the means of duplicating that unique volume, which is filled with sewn collages of varying materials and patterns. Solodkin incorporated lithography, embroidery, appliqué, and various kinds of sewing, but also sought out the textile printing expertise of Raylene Marasco, of Dyenamix. Through digital printing and archival dyes, Marasco recreated the patterns and textures of Bourgeois’s old and worn fabrics. The artist was extremely pleased with the results.

Bourgeois then made use of digital printing at Dyenamix for many of her late projects on fabric, which became her preferred support for prints. Such projects include Do Not Abandon Me (2009–10), a series in collaboration with British artist Tracey Emin, and To Whom It May Concern (2010), an illustrated book with poet Gary Indiana, both of which replicate the effects of gouache through digital means.

Etching

Bourgeois made use of hard ground etching relatively infrequently. Its fluid linearity appealed to her less than the more irregular effects of drypoint. Also, she preferred to stay away from acid, which is needed for incising etched lines into metal plates once they are drawn. In the 1940s, Bourgeois employed etching only on occasion. In the late 1980s, she was encouraged to take it up again by publisher Ben Shiff of Osiris and made a number of prints in the technique, working with Wingate Studio in Hinsdale, NH.

In her early period of printmaking, Bourgeois worked also in soft ground etching, a technique that usually involves drawing compositions on paper laid over plates covered in a waxy ground. Soft ground can capture the subtle qualities of pencil or crayon lines and, in the last decade of her life, again working with Shiff, Bourgeois took advantage of its potential for a major series of works, printed with Wingate Studio. The publisher supplied her with long narrow plates that fit her work table, and she worked on them easily with her drawing tools. Some of the soft ground etchings that resulted were editioned; others became the basis of unique works with hand additions and, sometimes, collage elements.

Photogravure

Photogravure is employed primarily for transferring images onto printing plates, and Bourgeois occasionally used it for this purpose. Her first opportunity came in the mid-1980s, when she met printer Deli Sacilotto, a specialist in the technique. This was just before she returned to printmaking in a sustained fashion, and she made photogravures of existing drawings in response to several requests for works to benefit causes. She then varied the editions with colored inks and papers.

Bourgeois’s most concerted effort with photogravure arose from her desire to complete the edition of He Disappeared into Complete Silence, an illustrated book she had begun in the 1940s. She was distressed that she lost the engraved printing plates—since she routinely saved everything—and had the idea of making photogravure plates to replicate them, with Sacilotto’s assistance. This project did not get very far. She also attempted to reproduce the plates in engraving, with printer Christian Guérin. Ultimately a second edition of the book was completed in 2005, working with Harlan & Weaver, and the initial transfer of images was accomplished in photogravure, with Renaissance Press of Ashuelot, NH.

Drypoint

Bourgeois employed drypoint more frequently than any other technique by far, creating some 1,500 prints that make sole use of it, or adding it to combinations of other intaglio techniques. She liked the fact that the drypoint needle was easy to manipulate and that no acid or special equipment was required. She referred to the scratching as an “endearing” gesture, a kind of “stroking.” While it could not “convert antagonism,” something she admired in engraving, she liked the immediacy of drypoint’s effects, with its soft, irregular line and tentative qualities.

Bourgeois made drypoints in the 1940s, working at home, and took up the technique again when she returned to printmaking in the late 1980s, most often working with printer Felix Harlan of Harlan & Weaver. She chose it for some her most iconic print projects, such as the Sainte Sébastienne series, which led to a monumental print nearly 40 inches high, the portfolio Anatomy, with its catalog of body parts, and the illustrated book Ode à Ma Mère, which presents a range of her celebrated spider imagery.

Lithography

It is usually painters who are attracted to lithography, since marking the flat surface of a lithographic stone or plate most closely approximates painting. Bourgeois actually had no natural inclination for this technique, and when master lithographer Judith Solodkin of SOLO Impression brought two printing stones to Bourgeois’s house in the late 1980s, she did not respond with much enthusiasm. Bourgeois was already familiar with lithography, having learned it at the Art Students League in the early 1940s under the tutelage of artist Will Barnet. She made several examples at that time, during a period when she was a painter and had not yet turned definitively to sculpture.

Bourgeois’s friendship with Solodkin was probably the reason she pursued lithography later in her career, and she eventually made a considerable group of significant prints in the medium. She responded especially to the vibrant color effects possible with this technique, and particularly its ability to produce bright blues and reds. She also liked the fact that large editions could be made easily, and often chose lithography for benefit prints.

Relief

Bourgeois made a relatively small number of relief prints, which is surprising given that the cutting and gouging inherent to the process might make them a natural choice for a sculptor. When she took up printmaking in the late 1930s, Bourgeois began with woodcut and linoleum cut, on which she experimented at home without the need for specialized equipment. Her early attempts are ambitious in their use of multiple colors, each requiring a separate block. Bourgeois later said she did not actually like the traces of wood grain that are often the distinctive and sought-after element of woodcuts.

Bourgeois also made isolated examples of stamped prints, and rubbings from surfaces she carved—both relief processes—but she never turned her attention fully to these techniques. Examples of relief prints from late in her career were the result of others suggesting she try the techniques for translating particular imagery from drawings. By this time Bourgeois was working with professional printers, and they often piqued her curiosity about the potential effects of one medium or another.